The entire Battle took place from 15 July – 3 September 1916, with the British ultimately victorious. It was a part of the larger ‘Battle of the Somme’, in the North-West of France..

The South Africans’ part in this battle lasted from 15 – 20 July – six days and five nights of horror.

From Wikipedia, some basic numbers:

“The most costly action that the South African forces on the Western Front fought was the Battle of Delville Wood in 1916 – of the 3,153 men from the brigade who entered the wood, only 780 were present at the roll call after their relief.”

A Picture of my grandfather, Joseph Sparks Hand, while wounded, in ‘Blighty’.

1,735 were wounded and sent home to England, known as ‘Blighty’. My grandfather was one of the ‘lucky’ wounded, sent to England for treatment of a wrist injury and being gassed. He remained a member of the Wits Rifles until he was declared unfit for active duty during the Second World War – because of lung damage he suffered at Delville Wood.

A little history gleaned from my family, before telling of the Battle of Delville Wood:

My grandfather, in uniform during the 1914 fighting in German South West Africa (now Namibia).

My grandfather, in uniform during the 1914 fighting in German South West Africa (now Namibia).

After fighting in German South West Africa in 1914, then in Egypt to save the Suez Canal, the South African soldiers, among them the 3rd Battalion of the Wits Rifles, were sent to northern France. They spent three weeks ‘training’ in the trenches in Bailleul, a town in Northern France, on the north-western border with Belgium. Thereafter, the troops, as part of the 9th Division (mostly Scottish regiments), found themselves marching 107 kms south-south-east, across the French countryside, along winding lanes, past fields of growing crops, and on into destroyed villages where death surrounded them. Regiments from the 9th Division, were already fighting in villages south of their march. Our ‘boys’ – and they were boys of 18 and 19 – walked through Longueval which had been taken by the British, where men had died in droves, and shells were still falling. On the other side of Longueval they found a battalion of dead Scots in a sunken road, used as a ‘front line’. Ian Uys, in his book Delville Wood, wrote: “Men were standing in the firing position facing the wood. Not one of them would ever fire a shot again. They were all dead, hundreds of them – and everything seemed so quiet and peaceful. Only the movements of our regiment were to be heard, no shells or rifle fire, only dead silence…”

First sight of Delville Wood:

At 06:00 on 15th July 1916, the men first saw Delville Wood – or, as the French named it, ‘D’Elville’ Wood.

Ian Uys continues: “Our first glimpse of Delville Wood was one of great beauty – the stately trees and leafy undergrowth in the hazy dawn of a midsummer morning had such a peaceful look. Except for the quiet tramp of man and the periodical bursting of the German shells in Longueval all was still.” And then: “The enemy was believed not to have entirely vacated the wood – our orders were to clear a certain section and then to hold it until further orders.”

I heard a slightly different version of the South Africans’ orders – that they were to ‘hold the wood at all costs’…

The Clay-chalk-mud in which the troupes tried to dig their trenches.

You can be sure that the wood did not smell as good as it looked at first sight in that hazy dawn. It was definitely not welcoming. The German forces had held the wood and had mostly retreated, leaving their dead behind. It was almost impossible for the men to ‘dig in’ with just their trenching tools. They were on low ground where the Germans could see them and pick them off at will, so they fell to their stomachs and had to dig through the trees roots which were entangled in the clay they grew in, while lying down and trying to counter the enemy’s fire. After many exhausting hours, they managed to dig themselves into one- and two-man holes, deep enough to sit in, while piling the diggings on either side of the holes for further cover from the German snipers.

As they moved further into the wood, they discovered that the Germans had nailed horseshoes, as ‘steps’, to the trees, after removing the lower branches, and used the upper canopy for snipers’ nests, not all of which were empty!

As the South Africans fought their way metre by metre into the wood, they began to shelter in trenches left by the retreating enemy – along with rotting bodies and rats … Which gave rise to horrid diseases such as Trench Foot, Trench Mouth and Trench Fever.

Battle in the Rain

It rained heavily for much of the battle. The men’s boots filled with mud and sludge and their legs were soaked, as their waterproof capes only kept the rain off their shoulders and upper bodies. There was nowhere to lie down or even sit comfortably, and also no chance of sleep: the Germans constantly bombarded the South Africans with shells, with the tearing roar of gun and canon fire, with billowing yellow-green and dark, massed gas clouds that contained every deadly chemical other than mere mustard gas, as they called it. If a soldier was caught by a gas cloud before donning his mask, the effects were dreadful – blistering and burning of mouth, nose and lungs, leading to internal bleeding and death. Wearing the gasmasks was awful but saved lives. It was difficult to see through the eye holes, the protective-chemical-infused canvas scratched the skin, and stuck to the eyebrows if Vaseline was not applied to them before donning the ‘bag’. It was hard to breathe, and if anyone were to vomit while wearing it, they would drown, so they were taught to lift the canvas mask to just above their mouths if necessary.

The Sounds of War

The noise was incessant – the crack of rifle fire and rebounds off the trees, the crump of shells destroying trees and men, the screams and moans of the wounded, the roar of officers trying to control the action, the whistling of the ‘whizz-bangs’, the hiss of the gas.

Here is another quote from Delville Wood by Ian Uys: “The wood was often lit up by the rapid succession of explosions. Whole groups of men disappeared in the fire and smoke. Later, a heavy rain turned the shell-holes and trenches into mud-holes and ponds.”

Our men were often ordered ‘over the top’ of the trenches to attack the Germans, running over ‘no-man’s-land’ littered with barbed wire and bodies, the Germans rising from their trenches to meet them, firing from the hip with their rifles and then fighting on with bayonets at close quarter, and with fists when bayonets were lost.

A unit of South Africans became cut off from the rest, for three days without food or water, stranded with their wounded, their dead and their dying, before General Thackeray and his South African First Battalion managed to fight his way through to relieve them on 18th July.

The wounded who couldn’t walk:

The wounded were carried by the ‘coloured’ stretcher-bearers on canvas stretchers filled with rainwater and blood, across the sticky mud and blood that used to be undulating woodland, in and out of bomb craters and deserted trenches, often thrown to the ground if one of the bearers was hit or they had to duck for cover from the German snipers waiting for them near the infirmary that was set up near Longueval. (The term ‘coloured’ in those days of the first world war, was used for anyone who wasn’t of full European descent, I believe. These brave men of colour saved many of our white South African lives, something very few people know of or acknowledge.)

Bill’s knowledge:

Me, with Bill Russell, January 1995.

Me, with Bill Russell, January 1995.

A very dear – sadly departed – friend of mine, Bill Russell – helped me with a lot of my research for the book I wrote, finishing in 1995, which was specifically about my grandfather’s time in Delville Wood.

Bill had fought in the Second World War as a sniper, with older men who had fought in the First War. He said to me once, “The Germans were the superior soldiers in both wars!” Of course, I asked, “So why did we (the British and South Africans among them) win two wars against them?” After cleaning out his pipe bowl and refilling and lighting it, dear Bill puffed out some blue-grey perfumed smoke and replied, “The German soldiers fought like a machine. We were thinking!”

Bill also taught me to fight with a bayonet and how to fire a rifle – a one-hour course, of which I remember virtually nothing, other than that it would have been horrific having to do it personally and as automatically as was necessary during any war. I do remember that the yelling that the troops are taught during bayonet-training acts on the adrenaline as did the war-cries before gunpowder was invented, and probably after, rousing aggression in the fighter and fear in the attacked…

Visiting Delville Wood Memorial and Museum

Visiting Delville Wood Memorial and Museum

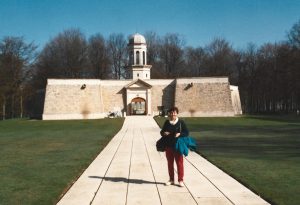

Me, on the path to the Delville Wood Memorial and Commemorative Museum at Longueval – 11th April 1995

In early May of 1995, I visited the South African Delville Wood Memorial at Longueval in France. This is South African property, bought by Sir Percy Fitzpatrick and given to the South African Government, along with Delville Wood itself, after World War I.

The wood, as my tour guide and I approached by car from Longueval, looked as beautiful, though not as green or as full, as it had on that morning in 1916 when the South African battalion moved towards it. Mist covered the ground, and the large trees, planted by South Africa to replace the awful battlefield it had become, rose high into the air, their branches shimmering with the pale green of spring.

I spent time in the museum and at the Monument – designed by Sir Herbert Baker, and now memorializing the South African fallen of both the First and Second World Wars. And I walked to the edge of the wood, where the single tree that survived the battle still stands. Blue crocuses were in bloom on the ground of the wood, blessing the dead who could not be retrieved, and covering the horrors of unexploded ordinance still there today.

Originally, the wood was mostly beech and hornbeam. It was replanted with a mix of beech and oak.

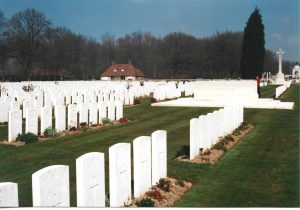

The Cemetery at Delville Wood – a haunted place in the spring mists.

The South African dead – only 151 of them, the others being buried in the ground of the wood during the battle, and irretrievable – are buried in an amazingly beautiful, though stark, cemetery, opposite the wood. Most of the plain white tablets that stand in long rows, commemorating the dead of the Somme region, are inscribed with the words, ‘Known only to God’.

Seeing that tree brought about the following poem:

Alone in springtime,

On shores of blue-flowered wood,

It stands.

Gazing towards once-decimated,

new-planted,

regimented ranks,

Where flying shells shrieked death –

In cool, blue shade it stands.

Deep are the scars

Of this fragile survivor.

Misty as the morning –

A glimpse,

A promise –

Of peace.

I’m sure we all wish that Peace could reign and all the weapons of war on display in military history museums, and all those currently in use and those being developed, would never again be necessary…

The Battle of Delville Wood, presented without pictures as a short speech to the Johannesburg Probus Club on 29th October 2024, by Isabel Bradley, at the Johannesburg Military History Museum.

Copyright, Isabel Bradley© 28th October 2024